It’s been 57 years, and I can still smell the revolution—is what someone from the Stonewall Riots might say today. And what a 57 years they’ve been for the LGBTQ+ community! Rights have been won, queer icons have come and gone, and a rich culture has evolved out of the adversity we faced along our journey—because nothing sparks creativity more than a little adversity.

In truth, nowadays, I think our straight counterparts are just a wee bit jealous. Gay culture is a beautiful, ever-changing thing that connects those who seek it out in our community. It bridges the gaps between generations. It teaches us how things were and how they are. It’s films, it’s art, it’s fashion, it’s pop divas and drag queens. It’s ballroom, the Club Kids, gender fluidity, saunas, BDSM, and circuit parties. Gay culture makes us laugh, cry, dance, and inspires us to fight for progress while not taking life too seriously.

One should always know their gay culture history, so we take a look back from pre-Stonewall to modern LGBTQ+ culture. To do almost sixty years of gay culture justice is impossible, but here’s a snapshot of where we’ve been, how we got here, and why the journey has been anything but straight.

Gay Culture in the 1960s and Before — Oscar Wilde, Judy Garland and Stonewall

It blows the mind that it was only half a century ago that gay culture existed mostly in the shadows.

Same-sex relationships were criminalized in many countries, and public exposure could mean imprisonment, job loss, institutionalization, or violence. As a result, early gay culture was coded, discreet, and survival-oriented, relying on underground networks rather than public visibility.

There had been gay icons, of course: the Irish poet Oscar Wilde; English raconteur Quentin Crisp; and Alan Turing (the man who cracked the Enigma cipher that led to victory for the Allies in WWII), for example. But all had suffered for their art through imprisonment, violence, and even conversion therapy. There had been rumored gay actors like Anthony Perkins and the swoon-worthy James Dean, but few could afford to be openly out. Many of our original divas go back to then too, with the likes of Judy Garland and Liza Minnelli championing gay rights long before it was en vogue to do so.

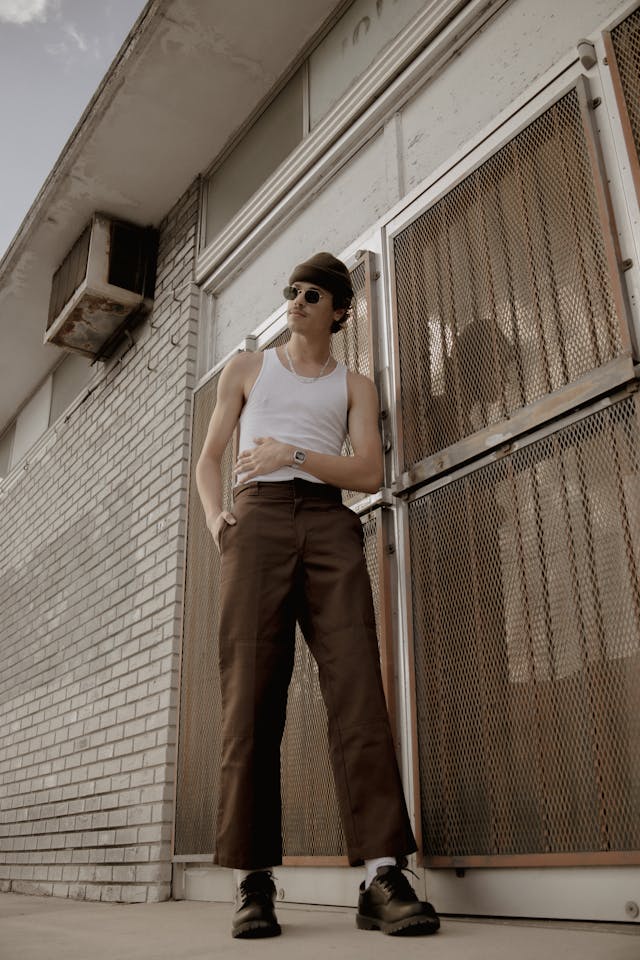

However, at street level, informal queer communities formed in urban centers around hidden speakeasy bars (often owned by the Mafia and other criminal organizations), private parties, and artistic circles. These spaces used subtle signals—fashion choices, language, or gestures—to identify one another safely. For many, identity was not openly declared but quietly understood.

Then Stonewall happened. One night in 1969, the patrons of the Stonewall Inn decided they had had enough after years of police harassment and fought back against a raid. The confrontation ignited days of protest and transformed queer identity from something hidden into something political—even if to this day no one can agree on who threw the first brick. The riots did not create gay culture, but they shifted it from secrecy to collective resistance, setting the stage for the liberation movements of the 1970s and beyond.

Gay Culture in the 1970s — Pride, Disco, and Sexual Liberation

The 1970s were loud, proud, and mostly unapologetically queer—I mean, the flares were your first clue.

In the wake of Stonewall, gay culture burst out of the shadows and into the streets. Pride marches (not yet the corporate-sponsored parades we know today) became annual acts of defiance and celebration. Coming out was increasingly framed not just as a personal decision, but as a political act. To be visible was to resist.

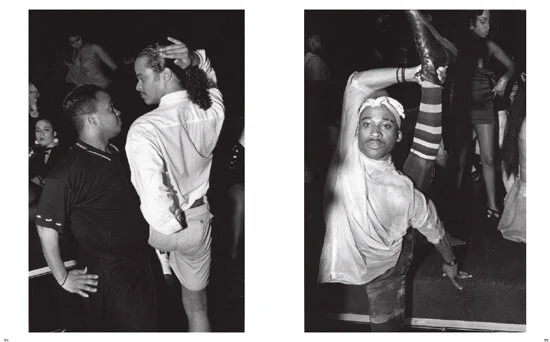

Disco music in the 1970s was deeply connected to gay culture, emerging from underground Black, Latino, and queer communities in cities like New York. Venues such as Studio 54 and underground discos offered environments where gender norms could be challenged through fashion, dance, and music. Artists like Donna Summer, Sylvester, and the Village People (especially the Village People!) pulled the gays out of hiding and onto the dance floor.

This decade also saw the rise of distinct gay neighborhoods—places like Castro Street in San Francisco and Greenwich Village in New York—where queer people could live, work, and love with relative safety. Gay bars multiplied, discos flourished, and nightlife became a central pillar of gay culture.

California, of course, was well ahead of the times and elected Harvey Milk as the first openly gay elected official in the U.S. Gay icons began to top the charts, like David Bowie (who identified as bisexual), Freddie Mercury, and Elton John, while cult classic films like The Rocky Horror Picture Show and Pink Flamingos (written by queer director John Waters and featuring the drag icon Divine) hit the silver screen. Gay group travel emerged as a quietly radical cultural force in the 1970s, shaped in large part by pioneers like Hanns Ebensten, who ran his first gay group trip into the Grand Canyon then.

The sexual revolution profoundly shaped gay male culture in particular. With the availability of birth control for straight couples and fewer societal expectations placed on queer relationships, many gay men explored non-monogamy and communal intimacy. Gay saunas began to open. Drag and camp aesthetics gained visibility, while lesbian feminism and separatist movements carved out their own cultural spaces and ideologies. The leather, BDSM, and fetish communities emerged as powerful expressions of post-Stonewall sexual liberation, rooted partly in postwar biker culture and partly in resistance to sexual shame.

While liberation rhetoric thrived, the decade also exposed tensions around race, gender, and class within the LGBTQ+ community—tensions that would continue to surface in later years. Still, the overriding spirit of the era was one of possibility: the belief that a radically different future was not only imaginable, but attainable.

Gay Culture in the 1980s — Icons, Ballroom, and the AIDS Crisis

The 1980s should have been our decade!

We dominated the music charts with the likes of Culture Club, George Michael, Dead or Alive, Elton John, Annie Lennox (OK, she wasn’t gay, but she might as well have been), Queen—the list is endless. The New Romantics might not have all been gay, but they couldn’t have been more gay if they tried. Films, theater, and fashion all bore the unmistakable fingerprints of queer creativity, even when queerness itself went unspoken or was deliberately obscured.

But sadly, the decade was shaped—defined, really—by the AIDS crisis. There are no words that can summarize what a tragedy that was, or that can do justice to the tens of thousands who died during that time. Modern-day TV series like It’s a Sin and Pose give a glimpse into how it felt to be gay then. What began as a mysterious illness quickly became a moral panic, with gay men demonized, ignored, or blamed for their own suffering.

In short, LGBTQ+ communities were forced to organize rapidly in response to stigma, government neglect, and mass loss of life. This period forged a culture rooted in mutual care, political resistance, and chosen family. Friends became caregivers, lovers became nurses, and entire communities learned how to grieve collectively while still fighting to be heard.

Organizations like ACT UP emerged to demand medical research, humane treatment, and public awareness. Gay bars, clubs, and community centers were more than social spaces—they were lifelines. Places such as the Stonewall Inn, already symbolic of resistance, took on renewed importance as cultural anchors.

There was still some joy left to be found, though. The ballroom scene, born primarily from Black and Latinx queer communities, flourished during this era. Through trans women–led houses, voguing, and elaborate competitions, ballroom culture provided safety, structure, and affirmation for those often excluded from mainstream gay spaces. The scene inspired Madonna’s “Vogue,” RuPaul’s Drag Race, and expressions like “throw shade” and “spill the tea” that we band around today. Paris Is Burning is the documentary that best shines a spotlight on this important scene.

Then there were the Club Kids, a flamboyant subculture that emerged in late-1980s New York nightlife, blending fashion, performance, and provocation. Organized by promoter Michael Alig, they transformed clubs like Limelight into surreal stages where gender was fluid, excess was art, and shock was currency. Club Kids rejected mainstream respectability, using outrageous costumes and public antics to claim visibility. Figures such as Leigh Bowery and RuPaul embodied this boundary-pushing spirit, influencing fashion and pop culture.

Identity during the ’80s era was often collective and defiant. Being openly gay was an act of courage, and gay culture emphasized solidarity over individual expression. Survival itself became a political statement—and in surviving, the community laid the groundwork for the battles, breakthroughs, and transformations still to come.

Gay Culture in the 1990s and 2000s — Pop Culture, Circuit Parties, and the Internet

The 1990s marked a turning point: gay culture began moving from the margins into the mainstream.

While the AIDS crisis still loomed large—particularly in its early years—advances in treatment and increased public awareness slowly shifted the narrative from inevitable loss to survival. Grief remained, but so did resilience. The community that had learned to organize in the 1980s now learned how to be seen.

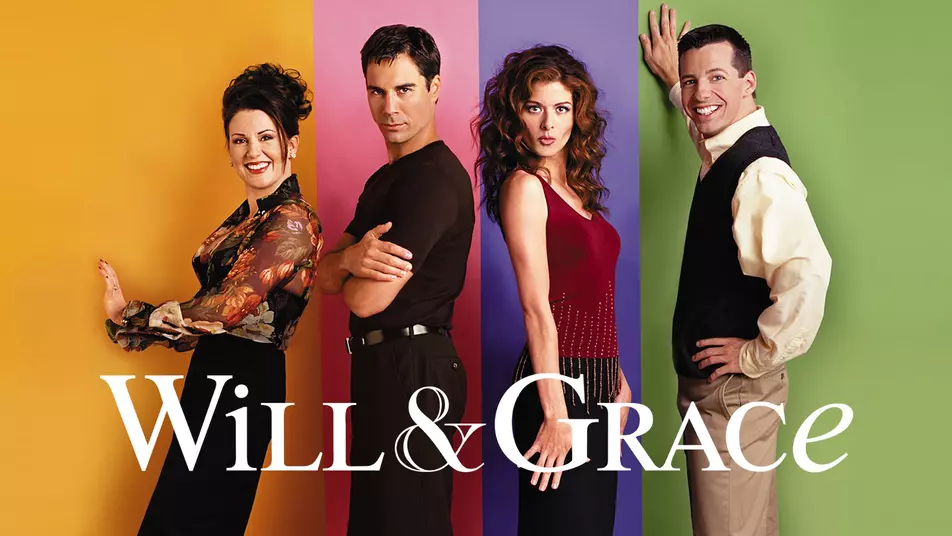

Visibility exploded across media. Television shows like Will & Grace and Queer as Folk brought gay characters into living rooms worldwide—one through sanitized sitcom charm, the other through unapologetic sex, nightlife, and politics. Films such as Philadelphia and Boys Don’t Cry pushed difficult conversations into the mainstream, while stars like Madonna, George Michael, and k.d. lang became cultural touchstones by openly aligning themselves with queer identity and activism. Public moments—such as talk show host Ellen DeGeneres coming out—further signaled a cultural shift toward acceptance.

The emergence of the internet quietly but radically transformed gay culture too. Long before social media, chat rooms, message boards, and early dating sites allowed LGBTQ+ people to find one another across cities, countries, and continents—often anonymously and for the first time.

This era also saw the global rise of circuit parties. What began as fundraising dance events in the late 1970s and 1980s—often supporting AIDS charities—evolved in the 1990s into massive, destination-based celebrations centered on house music, sex, and spectacle. Events like the White Party, Black & Blue, and Southern Decadence became rites of passage for many gay men. Alongside this, the kink and leather scenes—long present but often pushed underground—continued to thrive through leather bars, BDSM communities, and fetish nights.

By the 2000s, the focus shifted further toward equality within existing systems. Marriage equality became a central goal, and legal battles dominated queer politics. Gay culture increasingly emphasized normalcy—love, careers, domestic life—alongside nightlife and sexual freedom. While this era brought unprecedented rights and representation, it also sparked debate: what was gained through acceptance, and what risked being lost when queerness became palatable?

Gay Culture in the 2010s and 2020s — Grindr, Drag Race, and a Culture War

The 2010s ushered in a new era of self-definition.

Marriage equality was achieved in many countries, but instead of signaling an endpoint, it opened the door to deeper conversations about identity, power, and inclusion. Modern LGBTQ+ culture expanded beyond a single narrative, embracing a spectrum of experiences shaped by race, gender identity, class, and geography.

Television and streaming played a huge role in this shift. Shows like Pose, It’s a Sin, and RuPaul’s Drag Race didn’t just entertain—they educated, archived, and celebrated queer history and creativity. Drag entered a golden age of global recognition, turning performers into international stars and reintroducing camp, satire, and gender play to a new generation. Icons like RuPaul, Lady Gaga, and Frank Ocean embodied a queerness that was fluid, political, and unapologetically visible.

The rise of smartphone apps fundamentally reshaped gay culture (for better or worse), particularly through platforms like Grindr and Scruff. Location-based mobile dating apps were pioneered by gay men before Tinder became a thing. What began as tools for casual sex became the standard way of meeting men altogether—it’s hard to find a couple that didn’t meet through apps. Apps made connection instant and hyper-local, reducing reliance on bars, clubs, and cruising spaces, although some would argue this was very much for the worse.

Social media transformed how gay culture functioned. Queer people no longer had to migrate to big cities to find community; culture could be built online, shared globally, and reshaped in real time. Platforms like Instagram, TikTok, Twitter, and YouTube allowed queer people to find language, representation, and belonging without needing physical gay spaces. Everyone can now be a gay icon—you just need to grab enough attention to go viral.

Language evolved rapidly, visibility increased for trans and nonbinary people, and younger generations questioned binaries their predecessors had fought to dismantle. At the same time, backlash intensified. In what has been labeled a “culture war,” political attacks on LGBTQ+ rights—particularly targeting trans communities, drag, and sex education—made it clear that progress was not linear. Once again, culture became a site of resistance. Mutual aid networks, protest art, queer nightlife revivals, and a renewed interest in kink, leather, and alternative relationship models reflected a return to roots: pleasure as protest, visibility as survival.

The Gay Agenda Moving Forward

This retelling of gay culture history is sure to have missed something, as when looking at such a colorful tapestry, it’s impossible to count every thread. The best thing we can do when looking at culture is to simply seek out what interests us the most and find out more. Be that queer films, the leather scene or pop music.

As we push deeper into the 2020s, in a time shaped by pandemic, protest, and digital hyperconnection, we are left wondering what comes next for modern LGBTQ+ culture. A diplomatic ending to the culture wars? Digital divas? Queer AI overlords? Who knows, really. There’s not actually a “gay agenda,” but if there were, it would be to continue to gather, create, connect, and add to that beautiful, ever-evolving creature we call gay culture!

FAQ

How has gay culture evolved?

Gay culture has evolved from coded, underground communities focused on survival into a visible, diverse, and global cultural force. What began in secrecy grew into liberation movements, creative explosions in music, fashion, and nightlife, and eventually into mainstream visibility—while still retaining a strong tradition of resistance, humor, and reinvention.

What shaped modern LGBTQ+ identity?

Modern LGBTQ+ identity was shaped by a mix of activism, adversity, and creativity. Key forces include the Stonewall Riots, the AIDS crisis, queer art and nightlife, political movements for equality, and ongoing conversations around race, gender, and intersectionality. Each generation built on the struggles and freedoms of the last.

How has social media affected queer culture?

Social media has radically expanded access to queer community and culture. It allows LGBTQ+ people to connect across geography, share language and history, and create visibility without relying on physical gay spaces. At the same time, it has shifted how identity, activism, and even “gay icons” are formed—often faster, louder, and more globally than ever before.

What historical events influenced gay communities?

Major influences include the criminalization of homosexuality, the Stonewall Riots, the sexual revolution of the 1970s, the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, the fight for marriage equality, and more recent cultural and political backlash. Each moment reshaped how queer communities organized, expressed themselves, and fought for survival and recognition.

What is the future of LGBTQ+ culture?

The future of LGBTQ+ culture is likely to remain fluid, creative, and contested. As technology, politics, and identity continue to evolve, queer culture will keep adapting—balancing digital spaces with real-world community, visibility with resistance, and new expressions of identity with a deep respect for its radical roots.

Comment (0)